Happy encroachment of the season of mists and mellow fruitiness to all! Something wicked this way comes…

Firstly, I can’t pretend that this year’s Edinburgh Fringe outing for Tales of Britain was a huge success – choosing a LGBT+-friendly venue was important to us, but it was a bit of a shock to realise that they didn’t allow kids into the venue. Which – although of course Tales of Britain is not an actual children’s event – is a bit of a kick in the teeth for a family-friendly folklore comedy show, and although this was supposedly a licensing issue, it honestly strikes me as a bit sad for the LGBT+ community – the more family-friendly, inclusive events held in LGBT+ venues the better, I’d have thought!

Never the fewer, tales were still told, and Brother Bernard did take the chance to record Borders legend THE BROWNIE OF BODESBECK with the Scott Monument in the background, so nil desperandum whatsoever!

The remainder of our Scottish tour did give Brother Bernard a chance to swot up on a number of Caledonian folktales, travelling as far north as Loch Garve (home to a famously chilly Kelpie), via Loch Ness, popping by to visit the home of the great Thomas the Rhymer, and above all, embarking on a very thorough MACBETH pilgrimage, from Scone to Forres to Lumphanan to Dunsinane…

As well as already including my own retelling of the twisted history of 11th century King of Alba Macbethad mac Findláech in Tales of Britain, as ‘Macbeth and the Witches’, my obsession with Shakespeare’s play goes back even beyond the time I played a wounded soldier, servant and Banquo descendant in the 1991 Ludlow Festival production, with David Rintoul and Haydn Gwynne. Although my favourite play may be King Lear, I describe Macbeth as my favourite poem, because it has that urgency, the rhythm, it’s so relentless, so short by Shakespeare’s standards… and is so filled with rhyme, to boot. So spending a week or two literally walking in the late King’s footsteps was worth every moment – even spending two nights in what was essentially a builder’s hut in Inverness.

Our pilgrimage fittingly began with a special Macbeth exhibition at Perth Museum, which we only caught on its penultimate day. Of course, very nearly 1,000 years on, there’s really nothing tangible remaining from Macbeth’s day, so it was more of a theoretical exhibition, but it was awesome to behold a first edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles (which I hope to begin recording in instalments for Audible in the new year), and it was a wonderful primer for retracing the misunderstood ruler’s steps.

… As indeed was beginning our tour with Scone. I’ll admit, somewhere in my fluffy mind I had always got Scone, the site of the coronation of endless Scottish Kings, mixed up with the isle of Iona – their burial place. So it never occurred to me that Scone was very much landlocked. However, I never needed the real Stone of Scone to appreciate the historical significance of the place – and who’s to say at this stage where ‘the real Stone of Scone’ is? And how brilliantly perverse to begin our journey with the last word of the play!

Otherwise, geographical necessity meant that visiting other locales from the real Macbeth’s story had to be in a higgledy-piggledy order. One of the first places we stopped was at Birnam Wood, which is a wee suburb that makes surprisingly little noise about its historical – or arguably legendary – connections, besides an info board pointing out the ‘Birnam Oak’, a tree which was centuries from budding in Macbeth’s time, but was a stripling in Shakespeare’s day. You don’t need me to tell you all about Birnam’s role in the story, and besides, we’ll soon be returning to that bit…

In Inverness, I struggled to find the right spot to record a version of the story, and the castle was basically a building site, but as this glorious capital of the Highlands was probably the real seat of the ruler of Moray at that time – albeit long before this castle was built – it seemed to be the right place for it.

Next we came to “Macbeth’s Hillock”, a tiny campsite in Forres where they like to claim to have the real “blasted heath” where Macbeth was accosted by the Three Weird Sisters – or, let’s say, Three Weird Gender-Non-Specific Faeries, to try to remedy the legend’s centuries of unnecessary misogyny. This was probably the most gossamer-thin Macbeth site of our whole tour, a legend based on nothing – but it looked like a pretty nice spot to camp, anyway. And to camp about.

One of the greatest thrills was the far more convincing site of Macbeth’s Cairn, near the village of Lumphanan, west of Aberdeen. You see, the real history of the relatively honourable ruler Macbeth was that he oversaw the government of Moray for 17 years, travelling to Rome and being known for his Christian generosity – until the usurping son of the fairly deposed and beaten in battle King Duncan, Malcolm III to be, cosied up to the Saxons and returned north of the border with Earl Siward to steal the crown. First Siward triumphed at Dunsinane, famously… but it was at Lumphanan that he and Malcolm saw Macbeth’s head hit the ground, ushering in a whole new era for Scotland. A far more Norman one.

This part of the story encompasses at least three sites – the village of Lumphanan had a small marker (Plus a Blackadder Inn – this is the real land of the Blackadders!), then the site of the battle is said to the the nearby Peel of Lumphanan, and just over the road is the supposed real ‘Macbeth Stone’, where the poor sap’s head was hacked off, and best of all, the place where his body was taken to rest before transportation to Iona – ‘Macbeth’s Cairn’.

The Peel is a nice enough spot for a sandwich, but locating the so-called ‘Macbeth Stone’ was a real puzzler. Following directions from numerous sources including the Modern Antiquarian did not really help that much, and getting anywhere near involved going over the road, tumbling over two farm gates and wading through thistles and nettles until deciding which of the not very notable rocks the legend refers to. It was out of sight of the road, up on a verge.

Macbeth’s Cairn, however, was a lot easier to find – and it involved the kindness of strangers. We were worried about trespassing at Howeburn Farm, but the people who lived there were exceedingly kind, and allowed us to go up into their higher field to see the spot where Macbeth lay.

When you visit a lot of legendary sites, it’s all too usual to know full well that their significance is entirely made up by the locals, that they’ve staked a claim to a myth and that claim is really all you’re there to experience. But this cairn somehow seemed far more historically tangible than most sites – had the ruler of Moray been killed in a battle here, this seemed just the place where his decapitated cadaver would be taken for temporary Christian rest. And despite the sheep poo and the barbed wire, this lonely wee spot was one of the most stirring visits of the tour – highly recommended.

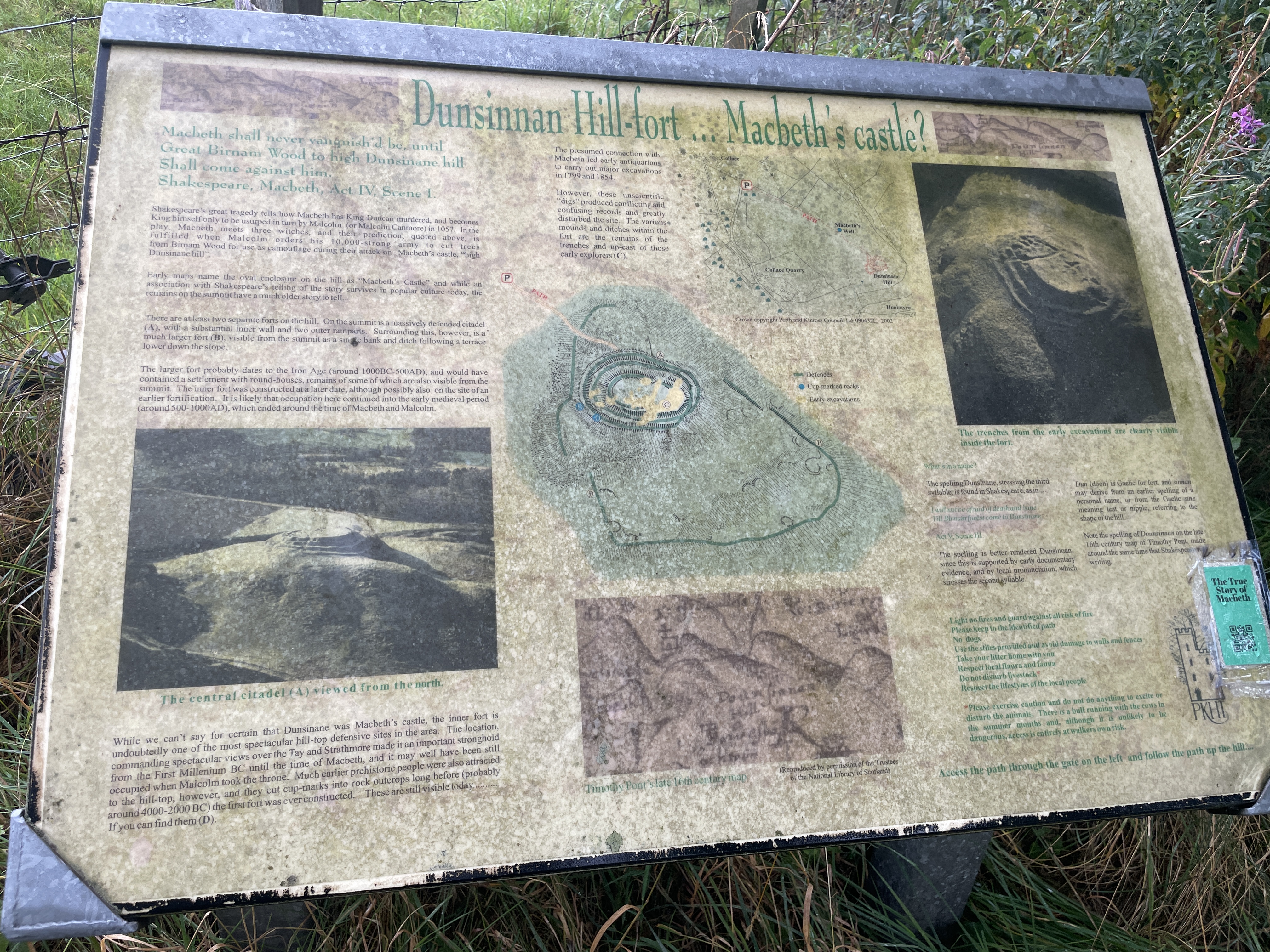

Our last stop-off on the Macbeth tour was perhaps the most famous site connected to the legendary King – Dunsinane Hill. In the play of course, this is where Macbeth meets his end, attacked by Malcolm’s army bearing leafy boughs from Birnam Wood – but the real historical record shows that Macbeth lost a battle here, where his southern castle was situated, and had to retreat to Lumphanan, where the real final battle took place.

I’m particularly keen to write about the visit here, as nothing online prepared me for the experience. Most of our Scottish holiday was bone-dry and sunny, but of course, just as we got to Dunsinane, a fair amount of dreichy rain had soaked the countryside all around, and I decided to head to the hill alone, so only I would have to get muddy and damp.

We found the tiny lay-by which served as the walking entrance to the hill, and I set off merrily enough… only after half an hour uphill, through a thorny, slippery and vague path, did I realise the enormity of the challenge I had set myself. I was in flip flops on wet ground, in a wet cloak, and only after a loooong and vague distance did the actual summit even become visible. I’m no stranger to irresponsible hikes and silly personal challenges, but it feels different when you have a wife and child waiting for you in the car. I could have very easily had a terrible fall up there in the Scottish drizzle – and it would not have been an easy place for any medical professional to get to. Be warned, if you ever want to visit.

It was perhaps the toughest hill-climb I’ve done to date – but after a while I was in furze “stepped in so far that, should I wade no more, returning were as tedious as go o’er”.

I wouldn’t have missed it for the whole throne of Scotland, though – a lifetime of fascination with the legend of Macbeth had finally led me to be standing victorious at the top of an awesome Scottish hill, Dunsinane itself, gazing out for miles around at the jaw-dropping country that Macbeth once claimed as his own, seeing the views he would have seen as his enemy drew near.

So foul and fair a day I had not seen.

Although, going by Google Maps, it wouldn’t have been all that easy to see as far as Birnam Wood back in the day: it is over 16 miles away…

I will aim to get my Macbeth story video edited and uploaded in time for Halloween, and hope that my on-the-hop storytelling in Inverness isn’t too ropey. But I thoroughly recommend a few days trying to untangle the lies, legends and propaganda of Holinshed, Shakespeare and co., paying tribute to the much-maligned Mormaer of Moray. Hopefully this travelogue will save you from a few wrong turnings and nasty surprises!

Ooh, finally, as we made out way back south of the border, we did stop off at Earlsdon, in the Borders, to pay a visit to Thomas the Rhymer, Scotland’s medieval answer to Nostradamus, who not only has his own Tales of Britain story, but also muscles his way into the Norfolk legend of The Peddlar of Swaffham in my retelling.

Sadly, we were annoyed to find that True Thomas’ tower, where he actually lived, is now part of a café which happened to be closed, so all we could do was look over the wall. However, the very site where Thomas was said to have been led into an underground faerieland by the Queen of the Faeries was worth going the extra few miles, marked as it is by a special stone (which does look a bit too like a gravestone, but heigh ho) at the foot of the faerie hill itself. This time, I did not go up it. And sadly we never saw any magical white harts.

Oh, and I almost forgot – we also stopped off for fish and chips at Loch Ness at one point, the site of another story in our book… albeit a narrative we had to pretty much make up from scratch, as there’s not a lot to the Loch Ness Monster myth besides “There’s this big monster in that big bit of water”. As it is, we did enjoy a paddle – the water was surprisingly warm – and nobody got eaten.

I thank my lovely wife for ferrying me around these legendary locations, and my son Nephew Neddy for being so patient as I explored them all.

We may not haste back to Scotland soon, when there are so many other mystical parts of Britain to be explored, but our solemn oath to travel the country, personally experiencing the real locations used in our folklore-fugged stories, is one we take very seriously. So, where next, I wonder…?

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow…